The Kinetic Chain: Why One Joint’s Dysfunction Affects the Whole Body

BLOGS

PhysioAlchemy

10/1/2025

Introduction

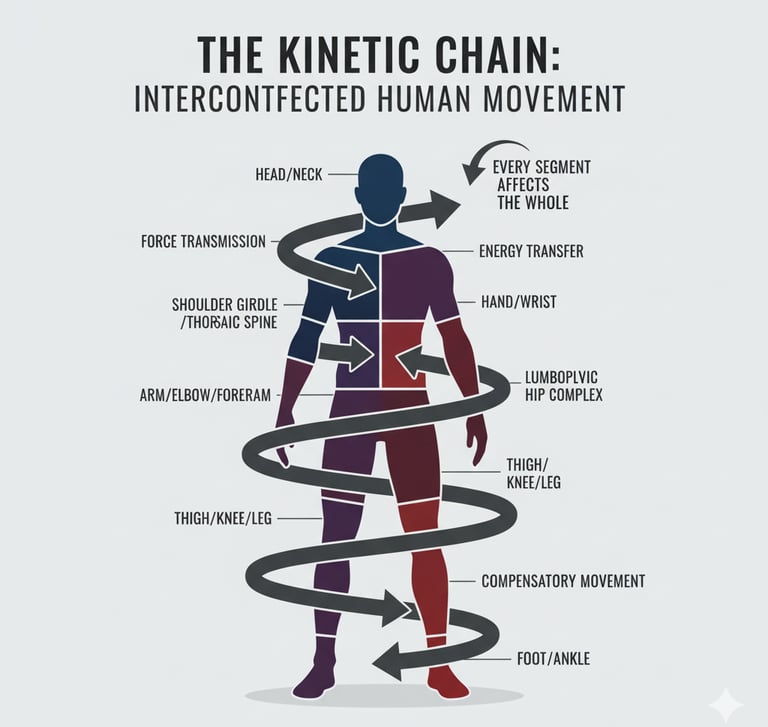

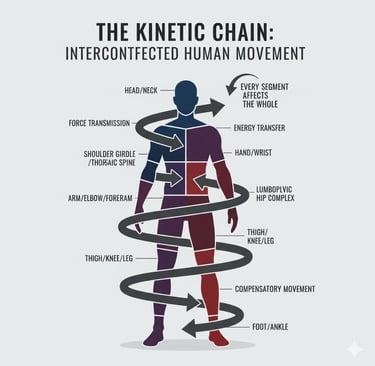

Movement isn’t a collection of isolated events. It’s an orchestra every muscle, joint, and nerve playing its part. When one instrument falls out of tune, the whole melody shifts. That’s what the kinetic chain is all about the seamless interdependence of the human body.

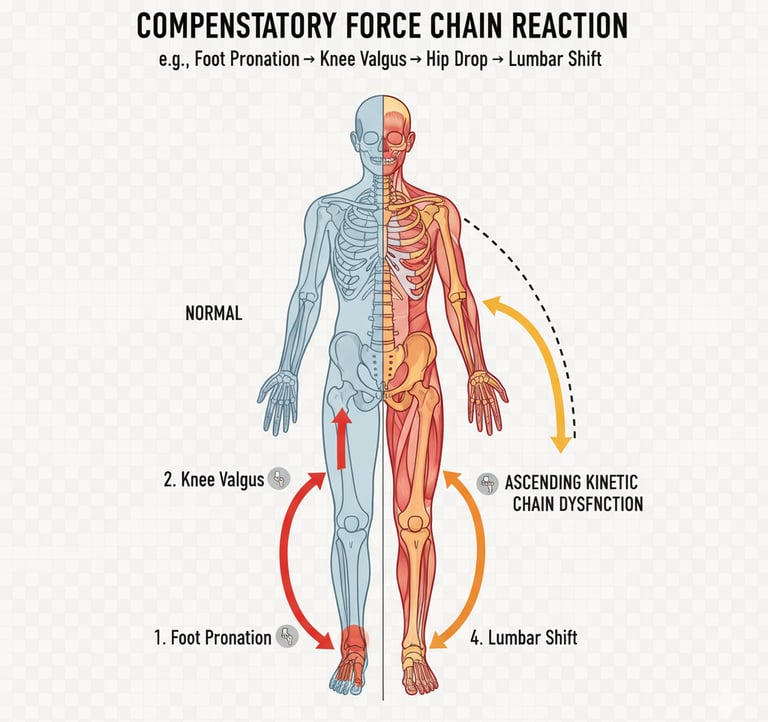

Every step you take, every throw or twist, involves force transmission from one joint to another. The body works as a chain of links, transferring motion, load, and control. If one link weakens, others compensate. That’s why a fallen arch in the foot can lead to knee pain, or why weak hip muscles often echo as low back discomfort. Understanding this principle isn’t just theoretical it’s foundational for precise assessment and intelligent rehabilitation.

The Concept of the Kinetic Chain

The term “kinetic chain” originated in engineering but was first applied to human movement by Arthur Steindler in 1955. He described the body as a series of overlapping segments connected by joints, where motion at one link influences the next.

We usually classify movement into two forms:

Open Kinetic Chain (OKC): The distal segment is free to move like swinging your leg while seated or doing a bicep curl.

Closed Kinetic Chain (CKC): The distal segment is fixed like a push-up or squat, where multiple joints move in coordination.

Most real-life actions are a fluid mix of both. Walking, for instance, begins as a closed chain at one leg and transitions to open at the other. The interplay between these forms keeps us balanced, efficient, and adaptable.

Anatomy of Interdependence

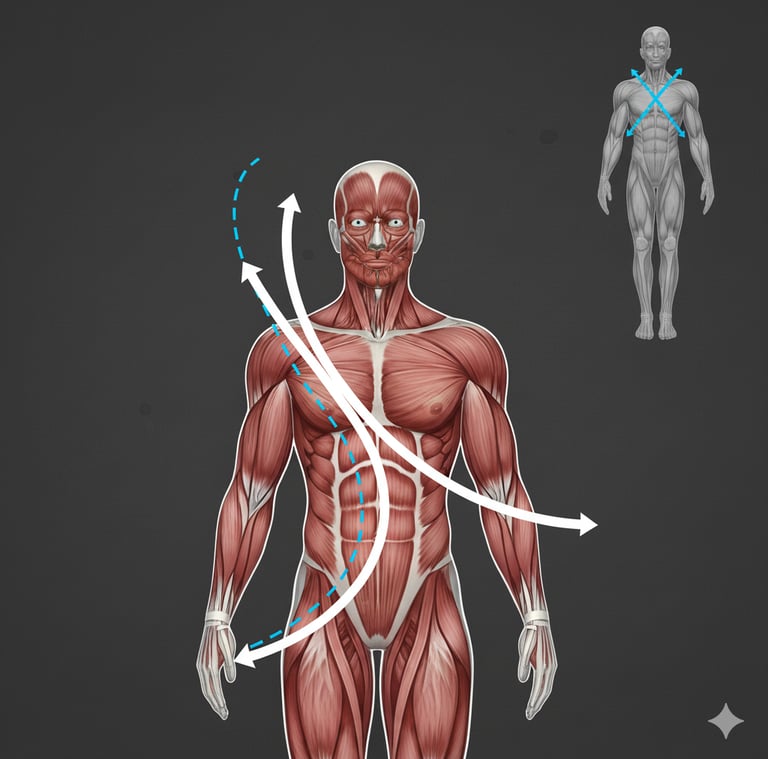

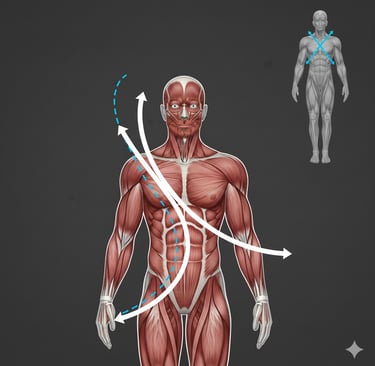

Each joint is more than a hinge it’s part of a living network. Forces travel through muscles, bones, fascia, and neural circuits. When you push the ground with your foot, the energy spirals upward through your legs, pelvis, spine, and shoulders until it reaches your fingertips.

This integration happens through three key systems:

Musculoskeletal linkage: Muscles and bones share forces through connected joints.

Neuromuscular control: Proprioception and reflex loops coordinate timing between segments.

Fascial continuity: The fascia forms long, continuous slings like the posterior oblique sling connecting the latissimus dorsi to the opposite gluteus maximus via the thoracolumbar fascia.

A restriction in one link tight hip flexors, a stiff thoracic spine, or inhibited glutes distorts this delicate balance. Movement then becomes energy-inefficient, and tissues compensate beyond their capacity.

Examples of Kinetic Chain Dysfunction

1. Foot–Knee–Hip Connection

When the arch collapses (excessive pronation), the tibia rotates inward. This subtle change travels upward, increasing knee valgus and stressing the patellofemoral joint. The gluteus medius loses mechanical advantage, setting off hip weakness and IT band strain.

2. Hip–Spine Interaction

Tight hip flexors tilt the pelvis anteriorly, forcing the lumbar extensors to overwork. Persistent lower back pain that no amount of stretching can fix unless the hip issue is addressed.

3. Shoulder–Neck Relationship

Scapular dyskinesis from weak serratus anterior alters shoulder rhythm, loading the upper trapezius. Over time, this pattern leads to neck stiffness and tension headaches.

4. Core–Extremity Integration

An unstable trunk fails to anchor limb movement. Whether it’s an ankle sprain or a tennis serve, poor core control turns efficient energy transfer into wasted motion.

Clinical Implications: Assessment and Diagnosis

Pain rarely tells the full story. A sharp knee pain might originate in a weak glute; shoulder discomfort might stem from thoracic stiffness. The best clinicians think globally, not locally.

Here’s how to approach it:

Observe movement, not just posture. Watch a patient squat, walk, or reach. Notice compensations.

Assess regionally. Look two joints above and below the symptomatic site a principle known as regional interdependence.

Use functional tests. Single-leg stance, overhead reach, or step-down tests reveal coordination flaws that static exams miss.

Identify muscle imbalances. Tightness and weakness patterns often coexist the trick is seeing both.

Rehabilitation Strategies

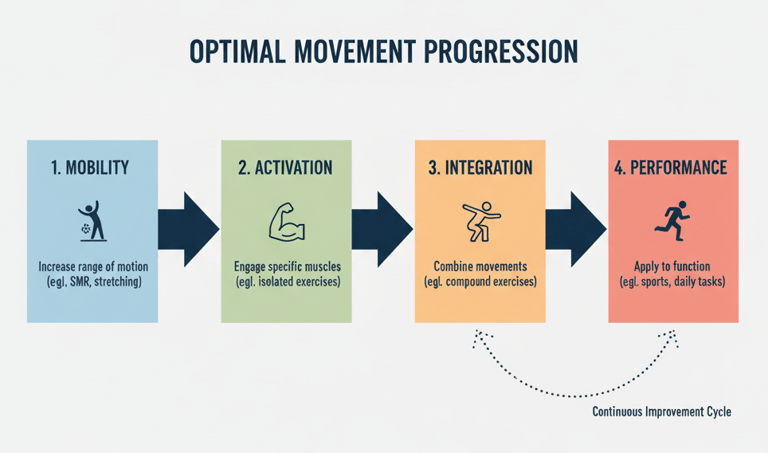

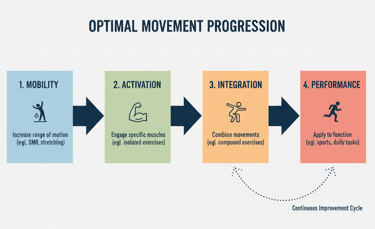

1. Restore Mobility

Start where motion is lost. Joint mobilization, myofascial release, or targeted stretching can clear mechanical blockages.

2. Activate Stabilizers

Wake up the deep muscles core, glutes, scapular stabilizers. They form the foundation for dynamic control.

3. Reinforce Integration

Move from isolated to complex: bridges evolve into single-leg deadlifts; wall slides into push-ups; breathing retraining into loaded carries.

4. Re-educate the Neuromuscular System

Balance boards, proprioceptive drills, and resisted movement patterns teach timing and coordination.

5. Train Functionally

Use multi-planar, closed-chain exercises. A patient recovering from ankle sprain should train hip strength and trunk balance not just the ankle itself.

Rehabilitation becomes effective when it respects the sequence of recovery restoring the chain, not just fixing a link.

The Kinetic Chain in Sports and Performance

In sport, efficiency of the kinetic chain separates the skilled from the exceptional. Take a baseball pitcher. The throw starts from ground contact, travels through the legs and hips, rotates the torso, and finally releases through the arm. Any energy leak say, poor hip rotation or weak trunk control reduces throwing velocity and increases injury risk.

The same applies to a sprinter’s start, a golfer’s swing, or even a dancer’s turn. The more synchronized the links, the smoother and safer the performance.

Conclusion

The kinetic chain reminds us that the human body isn’t a set of disconnected parts it’s an ecosystem. When one area struggles, others adapt. Some compensate successfully, others fail. As physiotherapists, our job is to listen to those adaptations to see how the ankle talks to the knee, how the hip whispers to the spine, and how the shoulder echoes through the trunk. Pain is rarely local; it’s the body’s language of imbalance. Treat the pattern, not the symptom. Restore the link, and the chain heals itself. That’s the art and science of movement.

Think Anatomically. Treat Clinically.

Our Socials:

© 2025 PhysioAlchemy. All rights reserved.

Legal:

Made with ♥ by physiotherapists, for physiotherapists.

Subscribe to our newsletter:

Enjoy exclusive special deals available only to our subscribers.